Ahmići: Croat war crimes and the denial of genocide

As part of The Hybrid Tours: Bosnia and Herzegovina Summer 2024 edition, we visited the village of Ahmići, in the Lasva Valley in central Bosnia. We did not anticipate spending long in the village, but when we arrived, we were greeted by Mahir effendi Husic, the local imam of both mosques in Ahmići. He showed us around a small memorial and museum established to commemorate the 116 victims and preserve the evidence of the massacre committed by Croat nationalist forces on the 16th of April, which was part of the wider Bosnian Genocide.

The village of Ahmići

The quotes in the following sections are from conversations with Mahir effendi Husic, the Iman of both mosques in Ahmići.

Until the 16th of April 1993, the population of Ahmići was approximately 800 people, about 90% of whom were Muslim. This also included 300 Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) refugees who had been forcibly displaced from other areas.

I’m glad you went to Srebrenica; I am glad that you are learning about what we’ve been through. I am honoured and proud that we were not behaving like that, that we as Bosnians were not destroying churches, not killing children, and doing those things and it’s important that you come from those peaceful countries to learn about this, it means a lot to us.

16th of April, 1993

Signalled by the early morning call to prayer, members of the Military Police and the “Jokers” a special unit of the Croatian Defense Council (HVO), attacked Ahmići. The attack had been preplanned by the HVO and given the military code name ’48 hours of ashes and blood’.

They came here to carry out this attack. They were prepared to do what they did

Even though the military code name suggests the attack lasted 48 hours, it did not last that long. The Croat forces attacked during the morning call to prayer, and it lasted until midday. All 116 victims were civilians. The oldest was 81 years old. The youngest was 3 months old. The baby was found in an oven. The Croats started their attack from the main road and concentrated their killing around the mosque before moving upwards.

The insignias of Croat nationalists who attacked Ahmići

Ahmići is a large village, and it rises further up. As people saw the killings happening, they started to run away and find refuge in the hills and forest above them before dispersing further away to refugee camps which were under the control of the Bosnian Army

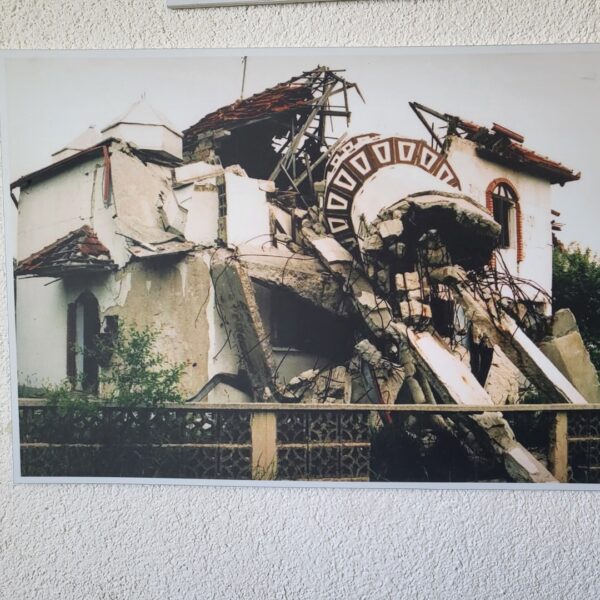

In addition to killing 116 civilians, more than 150 houses and stables were demolished and both the mosques in Ahmići were blown up. The photo of one of them, below, was destroyed by dynamite. When the Special Rapporteur’s field staff visited the village in early May, two weeks after the attack, approximately 180 destroyed houses were still smouldering. One of the mosques was also still smouldering.

“This is just one story from Ahmići; this mosque was built in 1991 and all the resources to build it were donated by Haji Hazi. While this mosque was being built in 1991 Catholic Croats nearby were building their central church, so Haji Hazi donated 20,000 marks for the church as a good neighbour. Only so that he would experience Croatian soldiers 2 years later. This isn’t a period of 20, 30, 40 years, this is a very short period of 2 years between him helping the church and then being killed when the mosque that he was building was destroyed.”

The village itself had no defence from the BiH soldiers because they were not there. The day before the attack on Ahmići, officers from the Bosnian Army were having a meeting in a nearby town with Croatian officers to plan activities together against the Serb nationalist forces. This attack was a betrayal.

They were pointing rifles at my husband and my son, and they told me to go and take my children with me…I hesitated, but I did not dare look at them, I looked down in front of me and they yelled at me to go and take my two children, because they would kill us all, and my younger son pulled me by my clothes and said, “let us go mum, so at least you stay alive.” Then I started with my children and they stayed there behind. I think I did not go more than 30 yards and I heard shots, I turned around, my son and my husband were falling down the stairs.” – Witness H (account from the Ahmići memorial museum)

“The attack on Ahmići was completely unexpected. All able-bodied men from this village were serving on the front lines in or around Sarajevo. There was no defence prepared for this at all. After the early morning call to prayer, the HVO started throwing grenades, Molotov cocktails and petrol bombs into the houses of the Muslims.”

The museum in the rebuilt mosque shows images depicting the direct involvement of their Croat neighbours. “These photos show our neighbours, our actual neighbours knew what was going to happen. This photograph (shown below) shows a Croatian owned house which is untouched, just opposite a Bosnian house which was burnt. Just a day before Croatian and Bosnian neighbours were having coffee, talking, and working in the fields together. The Croats knew what was coming because the night before they moved out of the village before the soldiers arrived. There was no indication from them to say oh my dear neighbour, why don’t you move with your kids. There was complete silence from them.”

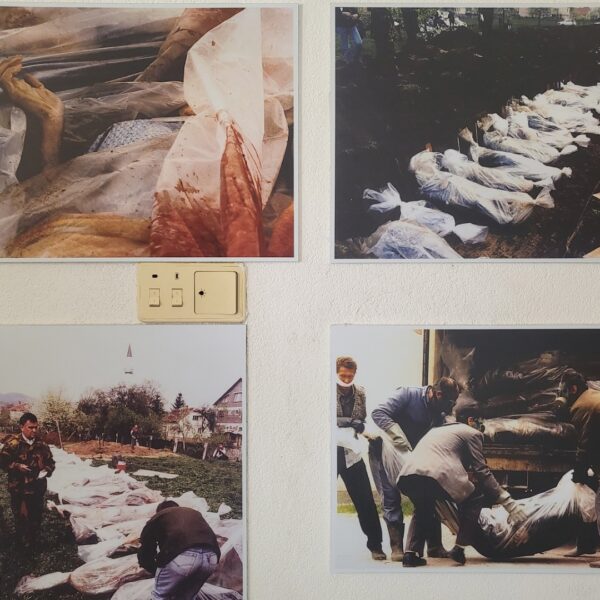

A British battalion arrived within three hours of the genocide. In a video taken by the battalion a soldier can be heard saying, “This is Europe 1993, not 1943.” The Battalion was the first force to enter Ahmići after the genocide and Bob Stewart, Commander of the Battalion, said it was a clear case of genocide. The British Battalion buried the burnt bodies in mass graves.

Discovering the genocide

To cover up their war crimes and how many people they murdered, the Croat forces were also burying people in mass graves. In 2021, through DNA analysis, the remains of bodies from Ahmići were found in a mass grave near Mostar, 250KM away from Ahmići. “It’s 2024 and we are still looking for the remains of some of the victims.”

Despite commanding the battalion that had first discovered the genocide in Ahmić and documenting the war crimes of the Croat forces, Bob Stewart called back to the UK within 7 days and was quickly forced to retire with the rank of major. He later said he had not wanted to retire and wanted to continue his career. He is a friend of the village and visits every 16th of April with some of the soldiers from his battalion.

In 1998, the process of returning to Ahmici and rebuilding the town started. The perpetrators of these crimes are still living in the village, but there is no communication and no context of them feeling awful about their crimes. The street, where the mosque has been rebuilt, is being used by both the victims and the perpetrators.

Burying the victims of the Ahmići genocide

“The events in Ahmići shows the complete betrayal and the true face of Croats in BiH because it was completely unexpected and unprovoked. We knew what the Serbs wanted, but this was a clear stab directly in the back. Thank you for coming here and listening to the truth. We are not making up anything, we are speaking facts, we were there and the justice and reward for all of this will come in the hereafter. We will rejoin those who suffered and who were wronged. It’s important to spread this message into your countries and to spread the truth.”

Tribunal trials and the denial of genocide

The Croatian political leadership in the 90s, led by Franjo Tudjman, tried to portray the genocide in Ahmići as an anti-Croatian hoax or as a story made up by the British peacekeepers who had originally reported the genocide. When this failed, Croat leadership tried to state that Ahmići was a legitimate military target, despite the only victims being civilians. This was to suggest that they were targeting the Bosnian Army, but things spiralled out of control. The ICTY trials established that Ahmići was not a legitimate military target.

After the genocide in Ahmići, the political and military leadership of the Bosnian Croats suggested multiple possible theories to hide their war crimes ranging to it being provoked by a mysterious Englishman to it being committed by Serbs or Muslims dressed in Croatian Defense Council uniforms. This cover-up continued after the war even when the ICTY issued indictments for the crime Ahimći. The Croat leadership forced the accused to surrender while simultaneously launched an operation to undermine the work of the The Hague tribunal to uncover their crimes during the Bosnian Genocide in an operation called “Operative Action the Hague.” Before the arrival of investigators from The Hague, the archives were moved to places inaccessible to them and cleaned of compromising documents. This was done to cover up their war crimes and place the blame on people who were less meaningful for the regime than Kordić and his circle.

The families of the ‘Hague prisoners’ received financial compensation from the Croatian state budget while several people connected with the genocide in Ahmići lived under false identities in Croatia. They were given houses by the state and the protection of the military security services. This lasted until Autumn 2000. This conspiracy was uncovered by the efforts of Zagreb lawyer Ante Nobilo. Ante represented Tihomir Blaškić, a HVO general and a war criminal, who was selected by Croat leaders in Zagreb and Mostar, to be the only one blamed for the crimes in Ahmići. Blaškić was sentenced to 9 years imprisonment for the inhumane and cruel treatment of Bosnian Muslims.

Even though Bob Stewart was one of the first people to witness the aftermath of the genocide in Ahmići and saying this was a clear genocide, The Hague war tribunal did not sentence the perpetrators for the crime of genocide but for crimes against humanity.

All those who were convicted for the crimes in Ahmići have now been released from prison, including Kordić, a warlord in the Croat controlled part of central Bosnia. He was sentenced to 25 years in prison where according to his own testimony he received revelations from Jesus Christ. He has since devoted himself to Catholicism and is a welcomed guest at Catholic vents throughout BiH and Croatia. Kordic was released 8 years and 4 months early.

In 2023 a video was released of Kordić saying, “When he asked me (a friend) if it was worth the imprisonment, if it was worth the war, I told him I would do it all over again, I wouldn’t exchange a single second.” Following the release of the video, The Association of Victims and Witnesses of Genocide, asked the president of the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals to review the 2014 release of convicted Bosnian Croat war criminal Dario Kordić. Their letter states “When a convict sentenced for the most severe crimes is released eight years and four months earlier than the sentenced term of 25 years, and then, after nine years, says they would do it all over again, they not only mock international justice, insult the victims, and undermine the international legal order, but they are also willing to commit new crimes.”

Croatian legislation continues to help genocidaries

The ongoing denial of the Bosnian Genocide is the last stage in the 10 stages of genocide. It is characterised by war criminals and their allies trying to refute the experiences of victims and the insurmountable evidence of their crimes. It is also characterised by the continued protection of war criminals. Croatia has taken genocide denial a step further and this year, war criminals like Tihomir Blaškić could legally ask for his criminal record to be erased because his statutory rehabilitation period of 20 years will conclude.

Despite being a commander in the HVO during the Bosnian Genocide, committing crimes against humanity and being sentenced to 9 years in prison, Blaskic could be the first war criminal to test the Croatian Act on the Legal Consequences of Conviction, Criminal Records and Rehabilitation, which ent into force in January 2013.

Article 18 of the Croatian law states “after the time limit specified by law has lapsed and under the conditions specified in [the act]… a perpetrator of a criminal offence is to be regarded as a person who has not committed a criminal offence, and his/her rights and freedoms shall be no different that the rights and freedoms of persons “who have not committed a criminal offence.” The act does not differentiate between people who have committed ordinary crimes and war criminals. The only exceptions are for those who committed crimes against children.

The act specifies that after the deadline outlined in the law, the judiciary will not provide any third-party data about a person convicted of war crimes. This means genocidaries, after they have served their sentence and after the period of time prescribed by the law, will be considered ordinary citizens without convictions. Their names will no longer be allowed to be used by activist, journalists, and others in relation to the war crimes they committed. Their records will be erased while the victims of their crimes will never be reunited with their families and in turn their families will have to live with the knowledge that they can never mention the war criminals name as the perpetrator of the crime against their family and friends without facing a defamation case.

Additional evidence related to the crimes in Ahmići can be found below:

Lt. Bob Stewart’s dairy entry 24th April 1993

Lt. Col. Stewart’s letter to Tihomir Blaškić, 22nd April 1993

Additional resources and publications about the Bosnian Genocide can be found below:

Blog posts

Want to learn more about the Bosnian Genocide? Here are 5 books we recommend.

Narratives

There is no substitute for rational thinking, it’s easy to get swept up in the lies (Zenica)

That’s where you feel the ethnic cleansing, in the silence (Banja Luka)

Is genocide a flavour of Gatorade? (Sarajevo)

It’s very sad to see history repeating itself, we never learn any lessons (Sarajevo)

Peace isn’t the absence of war, it’s the steps we take to stop war (Mostar)

I want people to embrace Srebrenica as a lesson about the dangers of ultra-nationalism (Srebrenica)

It’s our victory to come back to Srebrenica (Srebrenica)

Refugees are seen either as criminals or saints. (Sarajevo)

Genocide is happening now (Srebrenica)

Humanism is something we need to share (Stolac)

Podcasts

Raising awareness about the Bosnian Genocide with Georgio Konstandi